Brainstorm Digital: Crafting Magic In The Digital Editing Room

By Ilene Dube

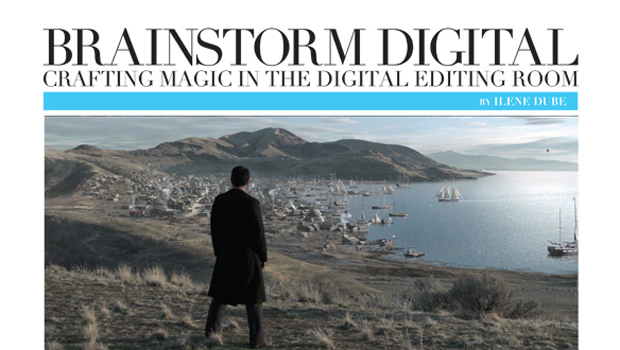

The world we see on the silver screen begins in the minds of directors, writers and producers. Creating that world so the rest of us can see it is no easy task. It requires complicated visual effects that, if effective, are “invisible.” We, the viewer, aren’t supposed to think about any of this, we just believe in the magic. Digital effects incorporate still photography, matte painting and computer-generated imagery to create environments that look realistic but would be dangerous, costly, or simply impossible to capture on film.

When the producers of Boardwalk Empire first envisioned turning Nelson Johnson’s book about a criminal kingpin in Prohibition-era Atlantic City into a TV series, they had to determine the feasibility of re-creating a world that no longer exists. They turned to Brainstorm Digital, a cutting edge innovator in the world of visual effects (VFX). Founded by Richard Friedlander and Glenn Allen in 2005, Brainstorm Digital created effects for such films as Angels and Demons; The Da Vinci Code; The Road; Frost/Nixon; The Adjustment Bureau; Synecdoche, New York; and Julie & Julia.

“None of that world of 1920s Atlantic City exists, and the producers wanted to see if they could re-create it in a reasonable manner and expense,” says Friedlander from his Manhattan office, where he is surrounded by state-of-the-art computer equipment. “They wanted to film in New York, but traveling was not an option, not even to the Jersey Shore.” Shooting on a soundstage was ruled out because it wouldn’t provide that authentic seaside boardwalk feel.

Using computer-generated imagery, Brainstorm Digital created a set to suggest Atlantic City, complete with period-appropriate billboards, arcade rides and streetlights. As with any project, it started with research: filming coastlines and recessed buildings at Brooklyn’s Brighton Beach. Archival photographs helped provide an overview of what the Atlantic City boardwalk looked like nearly 100 years ago. The original cityscape had completely altered. Buildings had been torn down and others erected.

Only 270 feet of set had to be built before visual effects could take over. The exterior set was surrounded by a giant blue screen several stories high made from shipping containers stacked like Legos. All this pre-visualization assured the producers that with assistance from Brainstorm Digital, the world of 1920s Atlantic City could be brought back to life. Once the pilot, directed by Martin Scorsese, started production, Brainstorm Digital was on the set.

“The city itself is a character of the show and we wanted to portray this world of 1920s crime and corruption,” says Friedlander. “We advised on where to shoot so we could add effects and have it be believable, such as shooting a scene offloading whiskey barrels in Brooklyn to stand in for the Port of Hoboken. Except for people, everything else is computer-generated.”

Instead of traditional paintings for the backgrounds, Brainstorm uses the latest software to create 3-D models of the hotels, piers and mansions of Atlantic City. Those models can be rotated and repositioned to allow for multiple camera angles—unlike two-dimensional paintings, which only work with a fixed camera angle.

Brainstorm Digital completed the pilot and the first three seasons, and then followed Scorsese to work on The Wolf of Wall Street. “That film has millions of effects but you wouldn’t know it,” says Friedlander. “If our work is successful, it is invisible to the general audience.”

Creating the waterways and gondolas of Venice, dropping in vintage buildings, bridges, stone walls and ships—there are countless hours that go into the research, creation and execution of these elements for what may only be on screen momentarily but will evoke a sense of place, era or mood. A doorway filmed in a small brick building can be made to look like a palatial Georgian Colonial; a house surrounded by development can be made to look like it’s in the middle of a green oasis.

Brainstorm Digital enables a film or TV show to create something that might not be practical otherwise. The Wolf of Wall Street was shot in New York but has scenes from all over the world. Frost/Nixon, also shot in New York, includes scenes of David Frost in London and Australia. “We added key landmarks such as the Sidney Opera House, using a painting of it,” says Friedlander.

Friedlander is part tech guy, part artist, part magician. “What attracted me to filmmaking and VFX is all of the above—we have artists on staff, creating visuals, and use tech and complicated experimental software and computer systems,” he says. “Some of our staff is more tech, some are more creative. Matte painters create the background. Compositors integrate what’s created in 3D into the shot to move with real objects. Sometimes it can take a few days, but Wolf was complicated—we spent 10 months to create something that appears on screen for 10 seconds.”

Both Friedlander and Allen have more than 20 years editing experience. A New York native, Friedlander landed his first job out of NYU Film School in the early ‘80s on Harry and Son, starring Paul Newman. “Newman needed a gofer and I was it. But he was down to earth, minimal, the opposite of what most people think. He helped me get into the editors union and upgraded me from assistant to apprentice editor.”

Friedlander also had the distinction of preparing Newman’s now-famous popcorn. The actor had just started Newman’s Own salad dressings and was “a serious popcorn eater. When he got hungry we’d do tastings on popcorn. Every day at 11 a.m. people would smell it being made. He was trying to figure out the best formula. I’d be popping popcorn, mostly fulfilling his enjoyment, but he’d coach me to taste for butter and salt.”

Dede Allen, the editor on Harry and Son, is considered one of the most creative in the industry. “Working with her opened opportunities for the work I did over the next 20 years,” says Friedlander. “I started on Apollo 13 with Ron Howard where I met (Brainstorm partner) Glenn Allen and started working as VFX editor with Tim Burton on Sleepy Hollow and Brian De Palma on Mission to Mars.”

Along the way Friedlander teamed up with Frances Ford Coppola, Arthur Penn, Warren Beatty, Dustin Hoffman, Peter Yates and Herbert Ross. He worked with Nora Ephron on Julie and Julia, using VFX to create the look of 1950s Paris, where Child was studying at Le Cordon Bleu. “We had to get rid of modern elements and signage,” says Friedlander. “Most of the film was shot on a set in New York, but when Meryl Streep looks out the window we had to put Paris in.” To make Julia Child tall, Streep was raised up on a platform—and VFX was used to erase the platform.

Friedlander and Allen first started Brainstorm Digital in Brooklyn’s DUMBO neighborhood, surrounded by artists and other creative types, back when DUMBO was the new Soho. The company moved to 37th Street in Manhattan at the end of 2013 to be closer to clients, and to lessen the commute for Allen, from New Jersey, and Friedlander, from Westchester.

Brainstorm finished 2013 with Wolf, and Starz Network’s Da Vinci’s Demons. Animal Rescue—the last film James Gandolfini acted in, a crime-drama centered around a lost pit bull, a wannabe scam artist, and a killing—will be released this year. Brainstorm just completed a remake of Annie, set in New York with an African-American cast.

Despite its capabilities to create illusions, Brainstorm does not do science fiction, but last year worked on the comedy Delivery Man, about an underachiever who discovers he's fathered 533 children through anonymous donations to a fertility clinic 20 years earlier. He discovers one son is a basketball player with the New York Knicks. To achieve the shot of the actor playing with the Knicks, a real game was filmed and a face-for-face replacement made. “We basically took the body and put a different head on. We changed the color of his hair, using photos made from every angle for a 360-degree model of a head and face to match into movements, lighting, expressions and dialogue.”

VFX is a growing business that studios and filmmakers are using more and more to create what can’t be done practically. “Even if it’s not cheaper, it looks better to scan a body and digitally put it back in than to throw a dummy off building.”

Even with two Emmy wins (Outstanding Special Effects in a Supporting Role, 2012, and Outstanding Visual Effects in a Series, 2011, both for Boardwalk Empire) and four Visual Effects Society Awards, Brainstorm is not ready to rest on its laurels. There’s a lot of competition out there—about half a dozen VFX companies in New York, Friedlander estimates. “But we were the first in New York for TV and films. New companies popped up after they saw what we were doing. Some are exclusively for advertising and commercials, more fantasy stuff—it doesn’t have to look real. We’re dirtying down and making it ugly to look like it’s really there. We make it look covered with dirt and dust.”