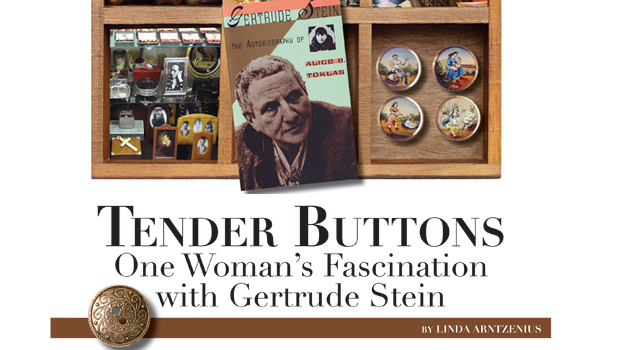

Tender Buttons: One Woman’s Fascination with Gertrude Stein

By Linda Arntzenius

There is a tiny store in New York’s Upper East Side with the name of “Tender Buttons.” The name alludes to a work by Gertrude Stein (1874-1946), a writer who has fascinated me since I first heard a 1934 recording of her reading her poetry. The title of Stein’s experimental book Tender Buttons, published in 1914, was all that was known to me of the book until last summer. I had never seen a copy until I stopped in at the Shakespeare & Company bookshop on a visit to Paris and discovered a new edition, published just this year, with illustrations by the San Francisco artist Lisa Congdon.

Shakespeare & Co. was an appropriate place to find such an obscure work by the enigmatic Stein. This unique little independent bookshop on the Left Bank opposite Notre Dame is what remains of the original, founded in 1919 by the American Sylvia Beach. Stein was the first to sign up for Beach’s famous lending library in the bookshop that was a gathering place for English-speaking expatriates in the period after the First World War. Beach’s generation was not the first to seek la vie de Boheme in the city of lights. Stein was among those who came to stay in the very early years of the 20th century.

The artistic and literary salon Stein created at 27 Rue de Fleurus, first with her brother Leo and then with her partner Alice B. Toklas, was also a gathering place. Practically every artist of note working in Paris at the time visited the two-story house near the Jardin de Luxembourg and the studio where Stein and her brother housed their collection of contemporary art. Beginning in 1904 with two Gauguins, a Cézanne, and two Renoirs, their collection of Modern Art grew to become one of the world’s most significant. Paintings lined the walls in tiers from fl oor to ceiling. By 1906, Leo and Gertrude had added works by Bonnard, Picasso, Matisse, Lautrec and more by Cezanne and Renoir.

On Saturday evenings, artists came to take a look at the paintings of their peers, which could not be seen in museums of the day. Over the years, these included artists Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Georges Braque, André Derain, and Henri Rousseau; poets Max Jacob, Guillaume Apollinaire, and Ezra Pound; and also writers Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Sinclair Lewis, and James Joyce.

In 1914, around the time that Alice B. Toklas, came on the scene, Stein’s brother left Paris for Italy, taking half of the collection with him. Toklas would become Gertrude’s life partner and apart from one brief encounter on the street, which Stein immortalized in her poem, “She Bowed to Her Brother,” Gertrude and Leo, who had been close to one another since childhood, were never to see or speak to each other again.

Presented on one of three CDs that accompany the book, Poetry Speaks: Hear Great Poets Read Their Work from Tennyson to Plath, Stein’s voice has a clear straightforward tone. Her diction is patrician and precise. Her words are not the least bit out of the ordinary—her vocabulary has been described as “childishly simple”—but the order of them within her sentences and the order of her sentences is unusual. Readers and listeners have a natural desire to find meaning in words. With Stein, one has to let go of this. By the time one has abandoned the search for meaning in Stein’s words, her hypnotic delivery has you in its thrall. Her poems are never narrative. They have a cinematic quality with a focus on “the continuous present.” She uses verbs with -ing endings, the present progressive tense, to create a feeling of continuous action. Perhaps this is why one finds it so hard to walk away from her work. It is happening now and it would seem almost rude to excuse oneself.

It is no accident that she and Picasso hit it off so well. Her most quoted line “a rose is a rose is a rose is a rose” almost defines the avant-garde and could serve as a catchphrase for the Cubist Movement (Cezanne was also an influence on her). Alice B. Toklas had the phrase printed on their letter paper and embroidered on their table linens.

First written as “Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose” in her 1913 poem “Sacred Emily,” where the first “Rose” is a name, Stein used variations of this line elsewhere in her writings. She once explained that it expresses the fact that using the name of a thing is enough to invoke all the imagery and emotions associated with it. In a sense, the rose as it appears in the work of poets down the ages is contained in that one sentence. As Stein said: “I’m no fool. I know that in daily life we don’t go around saying ‘is a ... is a ... is a ...,’ but I think that in that line the rose is red for the first time in English poetry for a hundred years.”

As poet C.D. Wright has observed “a noun ‘caressed and addressed’ by Stein stimulates the senses and rewards the alert reader.” It must be said, however, that not everyone finds Stein so captivating. The sound of her voice has been known to send guests scurrying for their coats. Although I hate to admit it, I have used this effect on more than one occasion, playing the recording of her reading to signal the end of the party.

Even today, her name elicits strong responses from critics. Although perhaps not quite as damning as in Wyndham Lewis’s essay, “The Prose-Song of Gertrude Stein,” in which he describes her writing as “infantile,” the result of her throwing words up in the air, catching them and “sticking them together again.” Whatever you think of Lewis’s assessment, he captures an essential element of Stein’s method: her playfulness. For Stein, words are tactile objects, almost, dare it be said, like buttons.

Her reading of “She Bowed to Her Brother” and “If I Told Him: A Completed Portrait of Picasso,” have formed such an impression in my brain that I have at times found myself emulating, not to say parodying, her characteristic rhythmic, repetitive style. “If I knew her would I like her. Would I like her if I knew her. If I like her do I know her. Do I know her if I like her. I would certainly bow to her. Certainly I would, would bow, to Gertrude Stein. Certainly I would. Wouldn’t you.” …That sort of thing.

Like the writings of Edith Sitwell, who visited Stein in 1924 and persuaded her to visit England, Stein’s poems must be read aloud to appreciate their full force. Her every word is exquisitely cadenced. The result is like music.

There is no denying that Stein gets under your skin. Her fascination with sound and syntax (she doesn’t use punctuation other than periods) transcends meaning, which is not to say that her work is without meaning, but rather that meaning is expressed subliminally, almost as a side effect of other aspects of her writing. To understand her one needs to realize that she was something of an experimental psychologist. She had studied at Johns Hopkins and earlier with William James at Radcliffe, then the female division of Harvard University before it opened to women. James called her his “most brilliant woman student” and encouraged her to enroll in medical school, but she really had no interest in medicine and left after two years without completing her degree. Instead, she followed her brother Leo to Paris in 1903. It was through Leo, that she became a collector and an appreciator of Modern Art.

Born in West Allegheny, now a part of Pittsburgh, she was the youngest of five children. Her father was a wealthy business man who moved the family to Vienna when Gertrude was three years old and then to Paris before settling them in Oakland, California. She wrote novels, plays, stories, libretti, and poems, including The Making of Americans: The Hersland Family. Her most famous and most accessible work is The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, a best-seller written in 1932. In spite of the title, it is Stein’s autobiography, a memoir of her Paris years, written in the voice of Toklas.

According to Hemingway, it was Stein who coined the term “Lost Generation” for those who came of age between the two World Wars. Hemingway describes Stein and the group who gathered around her in his memoir A Moveable Feast. The late biographer and novelist Janet Hobhouse presents a readable account of Stein’s life in her Everybody Who Was Anybody.

Three decades after she settled in Paris, Stein returned to America for a lecture tour in 1934. An electric sign reading “Gertrude Stein has Arrived” lit up Times Square and the newspapers had a field day with Steinese. Her lectures were well-attended but little understood. It was even suggested that she suffered from a psychiatric disorder (palilalia) causing her to stutter over words and phrases. Behaviorist B.F. Skinner weighed in, describing Tender Buttons as an example of automatic writing (a view that Stein dismissed). Others thought her magnetic, a compelling presence.

Thirty years later, in 1964, the late Diana Epstein bought a large collection of buttons from a store that had once belonged to a rather eccentric button dealer and, on a whim, opened her own store, Tender Buttons. Epstein was an editor for Funk and Wagnall’s Encyclopedia and one can only imagine her delight in the allusion. According to the store’s history as described on its website, antique restorer Millicent Safro stopped by for a button and, finding the place is need of some organization, offered to help out. Shortly after, she became a partner in the business and is now the sole owner. Stein would surely have loved the place.

Even if you aren’t looking to buy a button, the store is well worth a visit and odds are that you will come away with some curious item. Tender Buttons is a sort of museum with neatly arranged displays from a range of time periods and styles from all over the world. I spotted Art Deco, Art Nouveau, Japanese, Venetian, vintage, antique, scrimshaw, horn, amber, brass, silver, porcelain, crystal, cloth-covered, early plastic, pearl, shell, repousé, … you name it. Some have been made exclusively for the store.

Jennifer Reyes, who works there, estimates that there are millions of buttons. Pointing to the small box drawers that line one wall from floor to ceiling, she says that each contains hundreds of buttons and there are thousands of boxes. Perhaps the most precious are buttons from George Washington’s inauguration, she tells me.

On the first floor of a brick townhouse on a tree-lined street, the well-lit store is long and narrow, just eight feet wide, with a black and white checkerboard floor, small tables and chairs arranged down the center and a display of reference books by the founder. The novelist, Tom Wolfe, clearly an admirer, wrote the preface to Buttons by Diana Epstein and Millicent Safro (Harry N. Abrahms, Inc., 1991): “Inside packed haunch to paunch, shank to flank, elbow to rib, are people from all over the world indulging in the secret vice of setting themselves apart . . ..”

According to its website, it’s the only shop in America devoted entirely to the sale of buttons. “Each one is like a tiny evocative event,” says Safro. Stein might well agree.

Tender Buttons is Stein at her most abstract and experimental, a series of ruminations on small objects. Composer Virgil Thompson who set her writings to music for the operas Four Saints in Three Acts and The Mother of Us All, tells us that Stein came up with the title for Tender Buttons (and perhaps the concept for the book as well?) after seeing a sign for tiny mushrooms in a Paris vegetable market.

The book contains a series of still lifes with titles such as “A Carafe, That is a Blind Glass,” “A Substance in a Cushion,” “A Box,” “A Piece of Coffee,” and “In Between.” Lacking the rhymthmic repetitiveness of her poetry, it is not easy reading. Even her biggest fan, Alice B. Toklas described it as “impenetrable, hopelessly obscure.” One example will be enough to acquaint you with this mystifying work. Titled “Red Roses,” it reads: “A cool red rose and a pink cut pink, a collapse and a sold hole, a little less hot.” In the new edition of the work, Congdon illustrates this with an eight-point mounted stag’s head covered in pink fl owers on a mustard ground. The stag has a baleful expression. Need more be said?

Tender Buttons is Stein’s attempt to describe objects, objectively. I’m still endeavoring to wring meaning from it, even though I know that’s precisely the wrong approach with Stein. For if Stein has a message at all it is to let go and listen. Besides, success in fi nding meaning here might be tantamount to slipping inside the mind of the author. I’m not sure I want that. I might never fi nd a way to slip out again.