Reality vs Reputation – Setting the Record Straight on Modigliani

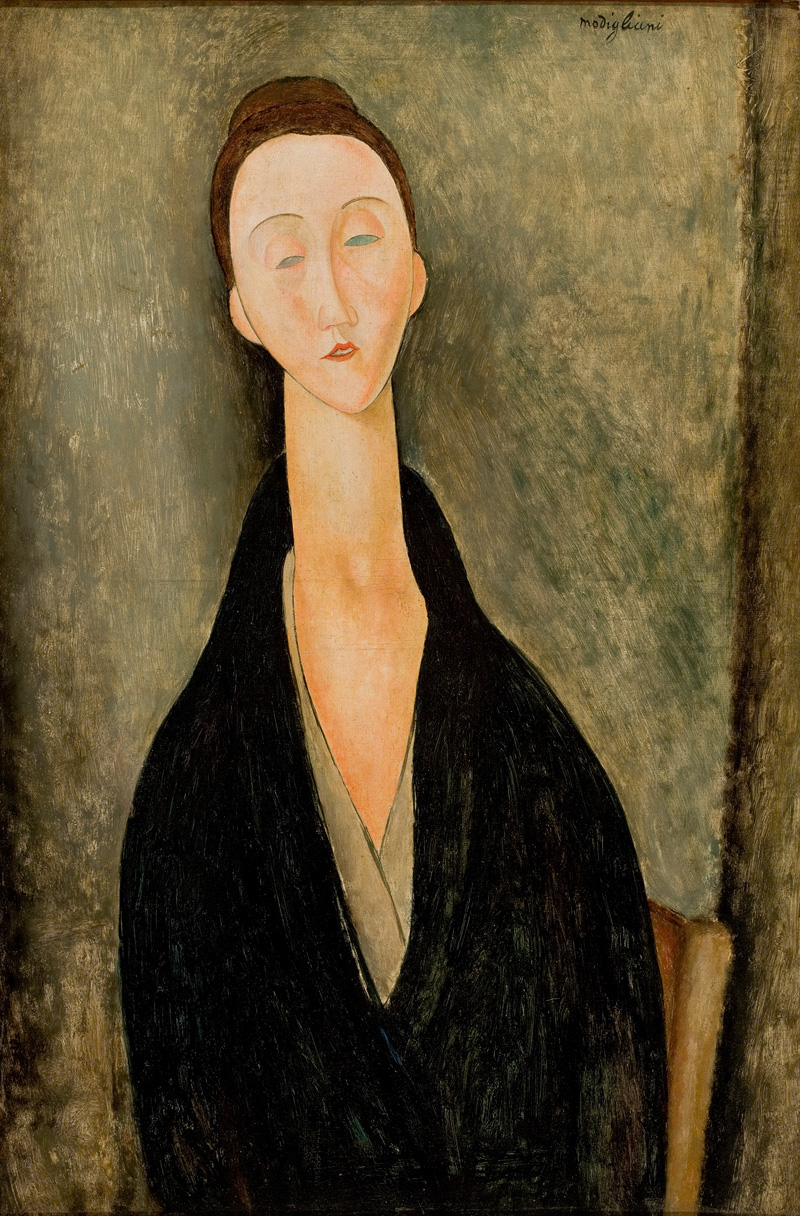

Amedeo Modigliani, Lunia Czechowska, 1919. Oil on canvas. Museu de Arte de São Paulo. Photograph by João Musa.

By Ellen Gilbert

“The exquisite-looking artist was often overshadowed by his Bohemian legend,” observed Jewish Museum Senior Curator Mason Klein at a recent press preview of the new Modigliani exhibit, “Modigliani Unmasked,” at the Jewish Museum in New York City through February 4, 2018. Images of Amedeo Modigliani’s movie star quality looks and accounts of his tempestuous and brief (1884-1920) life have indeed tended to overshadow his accomplishments, though sales of his later paintings in recent years do not seem troubled by these considerations: his Nu Couché fetched a whopping $170.4 million (with fees) at a Christie’s auction in 2015.

In the Jewish Museum’s new exhibit of early drawings and sculptures by Modigliani, Klein and his colleagues demonstrate how awareness of his background as a well-educated Italian Sephardic Jew who arrived in a Paris riven by anti-semitism is pivotal to understanding his work. Collected by Modigliani’s first patron and good friend Dr. Paul Alexandre, many of the works are being shown in the U.S. for the first time.

The Jewish Museum exhibition consists of approximately 150 works, including those from the Alexandre collection as well as a selection of Modigliani’s paintings, sculptures, and other drawings from collections around the world. Modigliani’s own art is set against representative works of African, Greek, Egyptian, and Khmer origin that inspired the young artist. At one point he stopped painting in order to develop his conceptual and pictorial ideas through drawing and sculpture.

Amedeo Modigliani, Unfinished Portrait of Paul Alexandre, 1913. Oil on canvas. Private collection on long-term loan to the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Rouen.

Among the works featured are an unfinished portrait of Dr. Alexandre, never seen before in the U.S.; impressions of the theater; life studies and female nudes, among them the Russian poet Anna Akhmatova; and drawings of caryatids and heads, which are telling of Modigliani’s sculptures, created over a five-year period from 1909 to 1914.

“Modigliani was the embodiment of cultural heterogeneity,” suggests the exhibit’s press release. In his native Italy he was never ostracized as a Jew, and although his dark complexion and fluency in French would have made it easy for him to assimilate in Paris, he chose to cling to his outsider status, often introducing himself by saying, “My name is Modigliani. I am Jewish.” His Nietzschean-informed notions about the superiority of artists also colored his behavior.

The exhibition catalogue, published by the Jewish Museum and Yale University Press, includes a compelling essay by Klein showing how close analysis of Modigliani’s portraits and figure studies in pencil, ink, gouache, and crayon reflect the artist’s “modernist embrace of difference, as well as an understanding of identity as heterogeneous, beyond national or cultural boundaries.”

Amedeo Modigliani, Study for “The Amazon,” 1909. Black crayon on paper. Paul Alexandre Family, courtesy of Richard Nathanson, London. Image provided by Richard Nathanson, photographed by Prudence Cuming Associates, London.

Special Events

A streaming audiotape for the exhibit is available and several special events are scheduled at the Museum:

“Tracing Modigliani” on Wednesday, October 25 at 2pm will give participants, under the guidance of Museum educators, an opportunity to create a portfolio inspired by Modigliani’s drawings and original source material.

Mason Klein will be the featured speaker at this year’s Salo W. Baron program (named for the preeminent scholar of Jewish History) on Thursday, October 26, at 6:30pm where he will continue his discussion of “how Modigliani’s work was influenced by the cultural melting pot of 20th-century Paris.”

Modern and ancient instruments incorporating the sounds of jazz, folk, Middle Eastern, and Latin music in an exploration of lost and forgotten Sephardic melodies will be explored in “Bang on a Can: Performance by La Mar Enfortuna” on Thursday, November 9, at 7:30pm.

Amedeo Modigliani, Head of a Woman, 1910-11. Limestone. National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, Chester Dale Collection.

Earlier Exhibits

This is not the Jewish Museum’s first foray into Modigliani’s work. Earlier exhibitions that included his more familiar portraits (the ones with elongated features) did not generate universal veneration. Writing about one exhibit in 2004, The Guardian art critic Robert Hughes declared that “If there’s one thing his show at New York’s Jewish Museum suggests, it’s that Amedeo Modigliani was probably never going to turn into a really great 20th-century artist.” Hughes was of the sickly, hard-living, attention-getting perception of Modigliani: his ability as an artist “hardly mattered from the point of view of his popularity, which is enduring and close to obsessive—not rivaling Van Gogh’s, of course, but cut from the same kind of material. The art audience loves a miserable loser who, after death, succeeds in a big way,” he wrote. “Not a fan,” Klein quietly said of Hughes when recently reminded of this article.

A 2004 biopic starring Andy Garcia that purported to tell the story of “Modigliani’s bitter rivalry with Pablo Picasso” earned an abysmal four percent rating on Rotten Tomatoes. “The best and maybe the only use to be made of the catastrophic screen biography of Modigliani is to serve as a textbook outline of how not to film the life of a legendary artist,” wrote New York Times critic Stephen Holden. Picasso biographer John Richardson gives the lie to the notion of a “bitter rivalry” between the two artists, noting that while Modigliani did not embrace the same styles as Picasso, “....Picasso had come to like Modigliani and his work well enough to acquire a major painting... and to sit him for a portrait more than once.” It was Modigliani’s addictions to drugs and alcohol that offended Picasso, Richardson says.

Biographies of Modigliani have not fared particularly well, either. “It shouldn’t be possible to write a dull life of Amedeo Modigliani, but [Jeffrey] Meyers manages the task,” said Kirkus Review of Meyers’s 2006 book. This reader was struck by Meyers’s awe at Modigliani’s fascination with the presciently surrealistic Les Chants de Maldoror, written in 1869 by Comte de Lautréamont (pseudonym of the Uruguayan-born French poet Isidore-Lucien Ducasse). Meyers wonders “how this repellent fantasy attracted readers as sensitive and intelligent as Modigliani and [Andre] Gide.” What is hard to imagine is Meyers’s curious notion that that radical art would not be recognized by others.

Meryle Secrest’s 2011 treatment of Modigliani’s life, which suggests that his flamboyant, brief life was more a result of his chronic tuberculosis and long-standing sense of doom, received a respectful review from art critic Holland Cotter, who appreciated the book’s “extended accounts of people, places, and events surrounding Modigliani.” Sue Roe also captures the ambience of the time in In Montmartre: Picasso, Matisse and Modernism in Paris 1900-1910.

Amedeo Modigliani, Caryatid, 1914. Gouache and ink on paper. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Bequest of Mrs. Harriet H. Jonas. Image provided by The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, New York.

Respect at the End

Modigliani’s work did not realize great sums of money in his lifetime; he originally asked his friend Jacques Lipchitz for ten francs for the painting he did of Lipchitz and his wife, Bertha. Thanks to exhibitions like this, our appreciation for the complexity of his work can only grow. It is good to know, though, that he was already recognized when he died. “It turns out that Modigliani did not fit the bohemian myth to the end, by dying unloved and unappreciated,” wrote critic Michael Kimmelman in 2004. “There was an enormous funeral procession for him to Père-Lachaise. Policemen who had arrested him over and over took off their hats as his flower-draped coffin passed. A rabbi said prayers over the grave. Many artists paid their respects: Picasso, Brancusi, Chaim Soutine, Fernand Léger, Gino Severini, Maurice Utrillo, André Derain, and Jacques Lipchitz.”

It was Modigliani’s Jewish compatriot Lipchitz who retrieved two other artists’ failed attempt to produce a death mask for Modigliani from the garbage; his moving result appears in this exhibit.