At the Dakota, Celebrities and Ghosts Mingle

By Ilene Dube

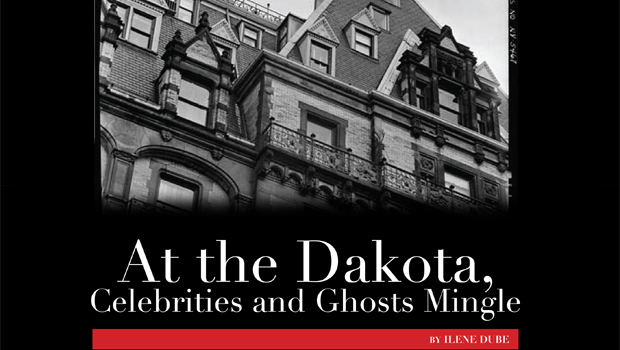

When Roman Polanski needed a building in which to set the satanic cults and witchcraft of the 1968 film Rosemary’s Baby, he chose the Dakota, at the northwest corner of 72nd Street and Central Park West. With its profusion of Gothic dormers and high gables, terracotta spandrels and balconies, it suggested hidden passageways to the occult.

The Dakota also had a role in the 2001 Cameron Crowe film Vanilla Sky. Protagonist David Aames, played by Tom Cruise, owns two apartments in the Dakota, elegantly outfitted with high-tech equipment and collectibles. And in Time and Again, the 1970 time-travel novel by Jack Finney, the protagonist visits the Dakota to conjure the year 1882.

Most know of the Dakota as the home of Yoko Ono, and the place where John Lennon was gunned down 33 years ago—the Strawberry Fields Memorial is just across the street in Central Park.

So how is it that a building so famous in movies, books and pop culture is shrouded in secrecy? When I phoned property manager Douglas Elliman and asked for stories about the Dakota, he wasted no time. “Absolutely not,” he said and slammed down the phone. Residents spending tens of millions on an apartment deserve privacy.

Lauren Bacall, Jason Robards, Leonard Bernstein, Lillian Gish, Rosemary Clooney, Roberta Flack, Jose Ferrer, Boris Karloff, Judy Garland, Rudolf Nureyev, Gilda Radner—these are just some of the celebs who have called the Dakota home ... or second or third home.

But star status is no guarantee of getting in. The persnickety coop board has denied residency to an equally impressive list: Billy Joel, Carly Simon, Antonio Banderas, Melanie Griffith, Cher, Madonna, Judd Apatow and Téa Leoni.

The most expensive Dakota apartment—the asking price was $25.5 million, although it sold for $21 million—was the second-floor unit where Leonard and Felicia Bernstein lived. With four bedrooms, four bathrooms, a great room with wood fireplace and park views, library, formal dining room, and a kitchen with breakfast room, it featured both original and restored window details.

Nureyev’s ornate gilded apartment was dubbed “The Nutcracker Suite.” Lauren Bacall paid $48,000 in 1961 for a cavernous upper-floor apartment, with views overlooking Central Park. She sold all her stocks to buy it, and calls it the only smart financial move she ever made. Signed photos of Robert Benchley, Noël Coward, Katharine Hepburn, Spencer Tracy, Lionel Barrymore, John Gielgud and Truman Capote line a wall of her parlor, according to an account in Vanity Fair.

To live in the Dakota, you must follow the rules: chauffeurs are prohibited from loitering in the lobby or distracting the doormen. Residents may use only firewood provided by the building, and they must take their luggage through the service entrance. Domestic employees, messengers and trades people are required to use service elevators, and childcare providers and “nurses/ companions” can only use passenger elevators when accompanying clients.

When hot dog vendors began showing up on 72nd Street in front of the building, staff made a call and police moved the vendors down the block.

The Dakota takes its historical relevance seriously; it has an aesthetics committee to review and approve renovation plans and tour each apartment before and after any work is done. No original fixtures may be removed.

New York’s most exclusive building was completed in 1884 in what was then a developing region of Manhattan. Elevated trains were running up Columbus Avenue, the Museum of Natural History was not far away, row houses were under construction, and Central Park had become a major tourist attraction. Edward Clark, who headed the Singer Sewing Machine Company, commissioned the architectural firm of Henry Janeway Hardenbergh, which also designed the Plaza Hotel and the Waldorf-Astoria (demolished in 1929 to make way for the Empire State Building).

Clark came up with the name Dakota because he was fond of new western territories. A Dakota Indian looks out from above the 72nd Street entrance. With its grandiose gables and courtyard, the Dakota may seem one-of-a-kind, but Clark and Hardenbergh had already built a similar structure five years earlier, the Van Corlear on Seventh Avenue from 55th to 56th streets. That 36-unit “French flat” survived until 1925.

On the Dakota, Hardenbergh and Clark spent $25,000 per unit, as opposed to about $8,000 at the Van Corlear, according to Christopher Gray in The New York Times. There was no dearth of bathrooms; each apartment had as many as four. “Nor did they suffer with a defect peculiar to the Van Corlear, whose courtyard had been used as an entrance for clattering grocer’s wagons and ice deliverers. At the Dakota the courtyard was for residents only. Deliveries were made in a below-grade turnaround, just under the courtyard.”

Even before the Dakota, Clark had been developing the Upper West Side. He’d built row houses on West 73rd Street, also designed by Hardenbergh, and had a vision for the neighborhood—the boilers of the Dakota also heated the 73rd Street houses. The property west of the Dakota was, for more than half a century, the Dakota gardens—with the boilers underground.

Designated a New York City landmark in 1969 and added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976, the square building is designed around a central courtyard. Its look was influenced by an amalgam of German Gothic, French Renaissance and English Victorian styles. Some of the rooms are nearly 50-feet long, with 14-foot high ceilings. Built for those with means— it was the fashionable place for New York’s high society to live—the Dakota featured amenities and a modern infrastructure considered exceptional at the time, with a large dining hall and dumbwaiters that could send meals up to the apartments. There was a playroom and a gymnasium, a garden, private croquet lawns and tennis courts. Some of these recreational spaces have since been converted to apartment space.

With ceilings of hand-carved oak and flooring inlaid with marble, mahogany, oak and cherry, all 65 apartments were let before the building even opened. Edward Clark wanted an apartment house that would be run like a hotel. In the early years, the Dakota had 150 employees: elevator staff, doormen, janitors, porters, watchmen, resident housekeepers, resident maids and laundresses.

Clark died in 1882 before the edifice was completed. Had he lived his own apartment on the sixth floor would have had floor-to-ceiling windows and a ballroom-size drawing room (24-by-49 feet). His son, Alfred Corning Clark, continued the project and also built the Dakota Stables on the south block of 75th between Amsterdam and Broadway. This Romanesque-style three story structure of brick and brownstone with a mansard roof had 145 stalls for horses and served as a club and office for coachmen and grooms. Edward Clark’s grandson, Frederick Ambrose Clark, sustained his grandfather’s vision in what was the golden age of the Upper West Side.

“Although its situation seemed enviable—the peace and quiet, the unobstructed light, the country air, the boundless vista—many New Yorkers thought the view to a vast greensward was a lonely prospect,” wrote Elizabeth Hawes in New York, New York, How the Apartment House Transformed the Life of the City (1869-1930). “It was a daring building and a daring venture.”

The influential mid-century designer Ward Bennett lived in an apartment created in 1962 from a warren of maids’ rooms tucked under the rooftop gables. It was legendary in the world of New York interiors, and in the news every time he redecorated it. In 1964 George O’Brien, who reported on home furnishings in The New York Times Magazine, called it ‘’the most exciting modern apartment in New York.’’

Lennon and Ono moved from a loft on Bank Street to the Dakota in 1973, taking up residence on the seventh floor and acquiring more space over time. They could often be heard rehearsing (although house rules stipulate no rehearsing at night). Sean was born in 1975, and John developed a reputation as a protective father.

Roberta Flack told The New York Times the Lennon apartment was uncluttered and tasteful, but in Life at the Dakota: New York’s Most Unusual Address (1979), author Stephen Birmingham found the Lennon apartment “wasn’t particularly stylish.”

The Lennons expanded beyond their two seventh-floor apartments, buying three more for storage, a studio for Ono and a guest suite. Annie Leibovitz’s famous Rolling Stone cover of a naked John Lennon embracing Yoko Ono was shot in Lennon and Ono’s apartment just hours before Lennon’s murder.

As the Dakota ages, so do its residents, and a $10,000 ramp was recently added to improve elevator access for, among others, Bacall, 88, who fell and broke her hip in 2011.

Just as with any old building, the Dakota has its ghosts—and not just Lennon’s, or echoes of Rosemary’s Baby. Several workers and visitors have reported sightings of a little girl in 19th-century garb and a 10-year-old boy dressed like Buster Brown. But for most of us, who will never get inside, there’s nothing to be spooked by.