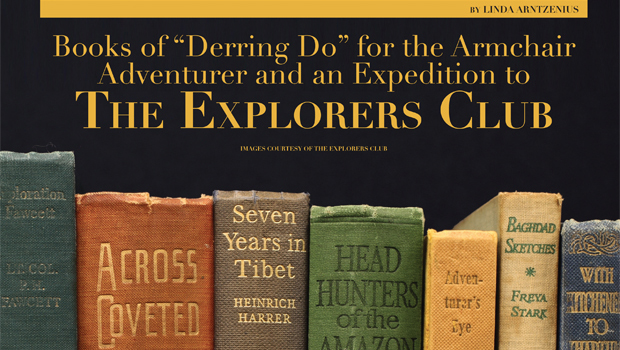

Books of “Derring Do” for the Armchair Adventurer and an Expedition to The Explorers Club

By Linda Arntzenius

Images Courtesy of The Explorers Club

Marco Polo, Ibn Battutah, Henry M. Stanley, David Livingstone, Mungo Park: their names ring with adventure. The records they left behind are classics enjoyed by countless armchair travelers. Sales of travel books peak during the holiday season. For what better time of year to enjoy a deathdefying yarn. Who can resist tales of eye-popping danger experienced vicariously from the safety of one’s own cozy fireside.

"As human beings, exploration is in our DNA,” says Alan Nichols an expert on Genghis Khan who has spent much time in search of the Mongol leader’s undiscovered tomb. Nichols is president of the Explorers Club which has its world headquarters on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in a six floor brick and limestone town house fi lled with curiosities from far-flung places.

Founded in 1904, the Explorers Club is dedicated to scientifi c exploration of the Earth, its oceans and outer space. Its members have been to the top of Mount Everest, examined the depths of the ocean, and walked on the moon. The most famous include Adm. Robert E. Peary and Matthew Henson, first to the North Pole in 1909; Roald Amundsen, first to the South Pole in 1911; Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay, fi rst to summit Mt. Everest in 1953; Jacques Piccard and Don Walsh, who went to the ocean’s greatest depth in 1960; astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins, first to the moon in 1969. Its famous women members (the Club didn’t admit women until 1981, now they make up a fi fth of the membership) include oceanographer Sylvia Earle (named Time Magazine’s fi rst Hero for the Planet in 1998) and primatologists Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey.

To step inside number 46 East 70th Street is to be transported to an era when the world seemed vast and maps still had regions of blank space marked “unexplored.” One can’t help but think of larger than life characters Lara Croft and Indiana Jones. Indeed some film industry location scouts have the club on their radar. It was used for scenes in The Verdict and Boardwalk Empire. And the imagined exploits the “most interesting man in the world” in the Dos Equis beer commercial owe much to the Explorers Club. But the advert’s montage of bravery—releasing an angry bear from a trap, catching a marlin Hemingway style, arm-wrestling or surfing a massive wave—pale in comparison to the real life exploits of the Club’s intrepid members. Stay curious, my friends.

I’m not entirely sure that all of the current members would approve this focus on adventure and “derring do.” Today’s scientific expedition organizers often regard “adventure,” as a byword for lack of planning and try to preempt the sorts of mishap that befall our on-screen heroes. Nonetheless it is hard not to make comparisons, especially since many of the fictions were inspired by the Club’s members.

Roy Chapman Andrews, for example, is Indiana Jones to a T. In the 1920s, the famed paleontologist braved sandstorms, civil wars and armed bandits, while leading expeditions to Central Asia for the Museum of Natural History. He was the one who discovered the first dinosaur egg in the Gobi desert.

And who would not romanticize stories like that of Peter Freuchen who, when stranded in a Baffin Island avalanche, was forced to knock off the toes of his frost-bitten left foot with a hammer so that he could make it out alive. Doctors later amputated his gangrenous leg. Freuchen went on to further explorations in Greenland and the Arctic.

“Stories abound here,” says Will Roseman, the Club’s executive director, as he leads me on a tour of the house that is part museum and part English Country Manor.

Here’s a portrait of former Club President Carl Akeley (1864-1926). Notice his scarred visage? Akeley is one of the few people to have survived a leopard attack. How so? He thrust his arm down the animal’s throat, balled his hand into a fist until the animal suffocated. “All the while the cat was tearing at his flesh,” Roseman tells me. If given the choice, it is apparently preferable to be attacked by a lion than by the much more aggressive leopard. Who knew?

This is just one of the snippets of information I pick up on my visit. If I could be a member of any club, this is the one I’d choose. But here’s the rub. To join, one must actually be an explorer, and not of the armchair variety. One must have taken part in some form of scientifi c exploration or fi eld research and must be sponsored by two current members. So as intrepid as I might feel (and I do) about my own independent travels, across Pakistan from Rawalpindi to Kashgar in Xingiang and on to Urumchi and Dunhuang on the edge of China’s Desert of Lop, none of it counts. No advancement of science, no membership.

In spite of my lack of credentials, however, Roseman continues to point out items such as the towering polar bear from the Chuckchi Sea between Alaska and Siberia (it roars at the touch of a hidden button).

The building alone is worth a visit for its history and architecture, its exquisite “linen fold” carved wood paneling from the 15th and 16th centuries. Built in 1912 by Stephen C. Clark, grandson of the co-founder of the Singer Sewing Machine Company, it was acquired by the Explorers Club in 1965.

The Members Lounge was once the Clark family drawing room. The coffee table was once a hatch cover on board the survey ship Explorer that survived the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 because it was out at sea. Here is a chair that once belonged to the Empress Dowager of Japan. There is another dating to 1574. Above the fireplace is a painting of extinct “Wooly Rhinoceros” by paleo-artist Charles R. Knight (almost blind when he painted it, he knew the animals from their bones). At the turn of the last century, Knight specialized in dinosaurs and prehistoric animals and his murals are in the world’s great natural history museums. The Club also has the original paintings by William R. Leigh that were made for dioramas in the Museum of Natural History’s Hall of African Mammals.

Roseman shows me the globe used by Thor Heyerdahl when planning his Kon- Tiki expedition across the Atlantic. In 1947, Heyerdahl and his 5-man crew sailed Kon-Tiki, a balsa wood raft, 4300 miles from Peru to Polynesia, suggesting that prehistoric South Americans could have originally settled the islands of the South Pacific.

Upstairs in the Clark Room where regular Monday night public lectures take place— George Clooney and Sandra Bullock showed up recently—are expedition fl ags that have been retired from the field after being carried across the globe and even into outer space. The crew of Apollo 15 took one to the moon in 1971.

The trademark Explorers Club flag is red, white and blue, with a diagonal stripe, the letters E and C, and a compass rose. It’s a sort of seal of approval and the same flag would often be carried on multiple journeys, until it had become too fragile, or too precious, because of where it had been, to be risked on further travels.

The first flag went to the Gobi Desert in 1925 with Roy Chapman Andrews. More recently, filmmaker James Cameron took the same flag that had been to the top of Everest to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, so that it would have been to both the highest and lowest points on Earth.

“At a recent talk the speaker asked the audience how many had climbed Everest and 16 people raised their hands. At most cocktail parties, there is usually one person who stands out, the one interesting individual everyone wants to talk to. But here, everyone is interesting,” Roseman laughs. A member since 2007 and the current mayor of Carlstadt in New Jersey, Roseman was once a bush pilot in the Congo.

We pass the sledge used in 1909 by Matthew Henson and Robert Peary on their expedition to the North Pole. Sunlight streams through the antique stained glass mullions of a large bay window that opens onto an outdoor terrace with a 15th century French cloister. The room’s magnificent stone fireplace with carved merman was originally in the British Museum. Above it there’s a statue of Joan of Arc on horseback and in full armor.

Over the fireplace in the Library is a painting by Albert Operti. Its title records with scientific precision: “Camp Clay Rescue of Lieut. A. W. Greely and Party, Sunday Night, June 22, 1884 at 11 o’clock.” Adolphus Greely, who would later become the Club’s first president, led an expedition to establish an American outpost at the edge of the Arctic Sea in 1881. His party was stranded on the ice for two years before they could be reached. He and six others survived. They had resorted to cannibalism.

STANLEY AND ROOSEVELT

About 100 researchers a year consult the Club’s 15,000 volume library and archival treasures such as Stanley’s letters from Africa to the New York Herald, including one dispatch that was recovered from inside the boot of a man killed in a tribal war. The Club draws documentary and feature filmmakers, journalists, scholars, historians, and travelers. Its explorers number 3,000 in 30 chapters across the globe. “Meeting fascinating people is the best part of my job,” says archivist Mary French, as she selects a lantern slide of Teddy Roosevelt with the slain elephant that he brought back for the Natural History Museum. The image is hand-tinted, as fresh as the day it was made, incredibly detailed.

A frequent guest of the Clark family, Roosevelt led expeditions to East Africa in 1908 and to the interior of Brazil in 1913. His bedroom now serves as the office of the Club’s president. Roosevelt’s spirit permeates the building, especially in the Trophy Room that once served as a playroom for the Clark children and later a gallery for the family’s world class collection of modern art. Now, there are more pith helmets and African drums than Matisses and Renoirs. You’ll also find the skins of a lion and a leopard that Roosevelt shot. In the center of the room, is the long table on which his plans for the Panama Canal were laid out.

Here too is a stuffed Emperor penguin. In the corner are four contorted tusks from a single elephant; poor thing. There are a lot of elephant tusks here, as well as one from an adult male narwhal, an aquatic mammal from the Arctic. There’s even the tusk of a giant Wooly Mammoth of unknown provenance—the club isn’t a museum, so not every item is labeled and the origins of some artifacts are shrouded in mystery.

“Nowadays the club is devoted to conservation, it’s no longer the done thing to bring back trophy specimens,” says Roseman. I admire the circa 1900 cape made of cedar bark and wool by the Chilkats of Alaska. But what is this strange three-foot long object? Oh, silly me, I should have guessed. It’s the penis of a sperm whale, lovingly stuffed by some unnamed taxidermist.

The Club’s greatest treasure is not among its many curiosities however, but in a book, a treasure trove of knowledge and a very rare 23-volume first edition of Description de L’Egypte, chronicling the discoveries made during Napoleon Bonaparte’s scientific and military expedition to that country in 1798. This is the book that brought ancient Egypt to the attention of the world and led to the modern study of Egyptology.

The Explorers Club has weekly lectures and other events open to the public including a famously exotic annual banquet featuring dishes such as hog mask galantine, roast goat, pork chitterlings, sweet-and-sour bovine penis and mealwork maki. Fancy a bug covered strawberry? Anyone for scorpions on toast? Now that’s adventure for the strong of heart.

For more on the Explorers Club at 46 East 70th Street, visit www.explorers.org.