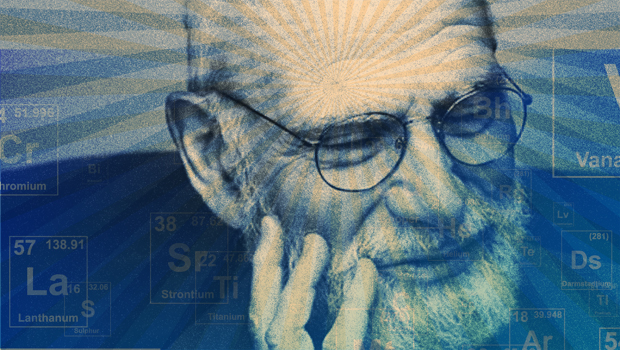

It’s Not Just The Disease – Oliver Sacks Wants Details

By Ellen Gilbert

"The hunger for narrative has been very strong for me, but also is a necessity for me,” observed Oliver Sacks speaking to an audience at the University of Warwick, where he was Visiting Professor in 2013.

The title of his talk, appropriately enough, was “Narrative and Medicine: The Importance of the Case History,” and Sacks, who has been referred to as “the poet laureate of medicine,” was making the case for the “complete integration of science and story telling.”

The London-born, 81-year old Sacks is nothing if not a master doctor/ storyteller, whose work cuts across genres. His book Awakenings, the basis for the 1990 film with Robin Williams and Robert De Niro, also inspired a play by Harold Pinter and a ballet by Tobias Picker and Aletta Collins. The Man Who Mistook his Wife for a Hat was the inspiration for a chamber opera by Michael Nyman and Christopher Rawlence, as well as Peter Brook’s L’Homme Qui... Sacks is also the author of Musicophilia and, most recently, Hallucinations. “His essays and books about people living with various neurological conditions have earned numerous awards and inspired millions of readers around the world,” his website succinctly reports.

Sacks was educated at The Queen’s College, Oxford, and is currently a professor of neurology at NYU School of Medicine. He has lived in New York since 1965. In addition to tackling a startling number and variety of medical conundrums over the years, he makes it a point to regularly speak out—quietly, but forcefully— about current events. “What do Rachel Carson, J. R. R. Tolkien, Aldous Huxley, William Styron, Toni Morrison, Galileo, Mark Twain, Judy Blume and Madeleine L’Engle have in common?” Sacks asked during Banned Books Week in an online tribute to librarians who have championed intellectual freedom. “Thank you, Doris Lessing, for your work and support,” he declared when the Nobel-Prizewinning novelist died in 2013. “You will be missed.”

Sacks’s 2002 book Uncle Tungsten was characteristically idiosyncratic. Subtitled “Memoirs of a Chemical Boyhood,” the book was described by science writer Natalie Angier as a “joyous, wistful, generous and tough-minded memoir.” In it Sacks details growing up in what he describes as “a medical household” where both parents practiced medicine using offices and creating lab space in the family home. “Table talk was always of medicine, and always presented in the form of stories,” Sacks recalled.

His mother, an anatomist and surgeon, “never lost the desire to go beneath the surfaces of things, to explain,” he told the Warwick audience. “Thus the thousand and one questions I asked as a child were seldom met by impatient or peremptory answers, but careful ones which enthralled me though they were often above my head. I was encouraged from the start to interrogate, to investigate.”

While Sacks claims not to remember medical school lectures he heard, he is quick to note that the building in which they took place is now “an ugly apartment building.” His impatience with dehumanizing practices came early: introduced for the first time to an emergency room he bristled when patients were identified by just their illness. To his joy, he discovered that “the one with a delirium” was a tea planter from Ceylon with fascinating stories to tell. Anxious that a later assignment at a migraine clinic in New York City would be dull, he was elated to discover “quite the reverse: migraine can provide a window into the nervous system.”

Patients’ stories about their suffering and the ways in which they coped with various ailments were, Sacks found, invaluable. When he was cured of his Sunday migraines, a mathematician Sacks was treating wanted them back, because they “cleared the decks of emotional debris, resulting in a surge of creativity Monday and Tuesday.” This willingness to compromise, says Sacks, “gave me some idea of the economy of an individual.” His father must have had a similar need to observe a person in context; encouraged at the age of 90 to give up making house calls he insisted that it was the one thing he would not give up doing.

Sacks is generous as he acknowledges others’ work, past and present. Since he casts a wide net in making sense of things, he may cite Shakespeare just as easily as he references William Osler, who is widely credited as the father of modern medicine. Osler’s observation that “it is much more important to know what sort of a patient has a disease than what sort of a disease a patient has” is particularly dear to Sacks. “Diseases and their effects are the same as they were for Hippocrates 2400 years ago, or for the writers of the Edwin Smith surgical papyrus,” he observes. “Whatever happens, one has to have good narrative— complete integration of the science and the story telling.”

Early in his career Sacks wondered about which of his contemporaries might write books that included nuanced case histories (as Wittgenstein noted, he says, a book should “consist of examples”) in which patients are presented as individuals, with details about their work, families, and how each of them coped and tried to hold onto their identities amidst illness. Such books would read like the “nonfiction novels” written by another of his heroes, Charles Darwin. An epiphany—“you silly bugger, you’re the man to write it”—led Sacks to write his first book, Migraine, which he describes as “little vignettes” of “biographies” that were “not too intrusive.”

For many people, the name Oliver Sacks will forever be associated with the 1990 movie, Awakenings. Based on Sacks’s 1973 book of the same name, it chronicles how, at a chronic disease hospital in the Bronx in the late 1960s, Sacks (played by Robin Williams) encounters dozens of people standing around motionless like statues. Told that nothing could be done for them, “I wondered what was going on in inside,” Sacks recalled years later. Encouraged by nurses (who “know more than doctors in chronic disease hospitals”), Sacks treated them with a newly available medicine, L-Dopa. “The first effects of this were lyrical and wonderful,” Sacks said. These people had been “dropped, as through a vacuum, from their 20s into their 60s. The world had changed beyond meaning,” and the challenge they faced as they tried to create new lives only strengthened Sacks’s belief that medical care “can’t be reduced to just giving a medicine.”

Sacks sounds bemused when he reports on the “mixed reception,” that greeted both Migraine and Awakenings. While they were well received by the general public, “a strange mutism” prevailed among his colleagues, and, lacking “the serious stamp of science,” no mention of either work appeared (at least for a while) in the medical literature. No matter. Sacks continues to tell stories about people who reorganized their environments according to color; to “see voices,” or who began to sing throughout the day as they valiantly rebounded from physical setbacks. And if medical science has been slow on the uptake, the public loves Saks’s messages. Writing in Slantmagazine.com about Sacks’s most recent book, Hallucinations, Tim Peters observed that “reading about a successful, well-respected medical doctor such as Sacks patiently describe that one time back in the ‘60s when he saw all the passengers on a New York City bus looking like bug-eyed aliens with smooth, white, ovoid skulls makes the prospect of you having a hallucination in your own life that much less socially and professionally damning.”

Sacks himself has no problem damning current trends in medicine. Recalling the “richly, beautifully descriptive” medical charts that used to capture the inner lives and imaginations of patients he decries the use of “mean lists of criteria” for making diagnoses (and enabling insurance reimbursement). A particular offender is the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistic Manual, which Sacks describes as “an abominable book.” Doctors may say they don’t have time to write a case history, says Sacks, “but one does have time. A deep and detailed case history doesn’t have to be long, if one uses language properly, it can be a couple of paragraphs.”

Sacks can be observed taking sips (it’s not clear of what) from his “favorite bottle” at speaking engagements these days and he sometimes pauses a little breathlessly between words. In July 2013 he wrote about his impending birthday in a New York Times op ed column: “Eighty! I can hardly believe it. I often feel that life is about to begin, only to realize it is almost over.” Still, the title of the piece was “The Joy of Old Age. (No Kidding),” and he is characteristically upbeat about the business of aging. “With a scattering of medical and surgical problems, none disabling, I feel glad to be alive—‘I’m glad I’m not dead!’ sometimes bursts out of me when the weather is perfect.”

There are, undoubtedly, many, many people who are also glad he’s alive and still very much engaged. It doesn’t come as a surprise to tune into a new Radiolab podcast, “Where Am I,” exploring how your brain keeps track of your body, and Sacks is the first guest, reporting how he is coping with his precarious sense of direction by carrying heavy magnets in his pockets that help to realign him when he turns as he walks. A recent message from his office, responding to a request for an interview was disappointing, but ultimately reassuring: “Dr. Sacks is not taking on any new commitments at this time—he is currently working on a deadline with his new book, and feels he must concentrate fully on the project at hand.”

In his op ed piece on aging Sacks observed that “perhaps, with luck, I will make it, more or less intact, for another few years and be granted the liberty to continue to love and work, the two most important things, Freud insisted, in life.”