Jack Kerouac’s New York

By Stuart Mitchner

Jack Kerouac’s earliest published writing on New York City appeared under the name John Kerouac, a formal touch reflected in the glossy, soft-focus, dust jacket photo and the relatively buttoned-up narrative style of his first novel, The Town and the City (Harcourt Brace 1950). When he celebrates the city as “the one place in all the roundway world where everything is different from anywhere else, simply because it happens in New York,” the only hint of vintage Kerouac is in a term like “roundway.” A long passage meant to suggest the mounting excitement felt by someone coming into Manhattan for the first time depends on generic expository prose about “the vital and dramatic heart” of the place and “the magnitude, the beauty, and the wonder of the great city,” phrases as detached from the spirit of his style as “John” is from the “Kerouac” who wrote On the Road.

In The Town and the City the excitement of arriving in New York is formally presented, as “an event of the most wonderful importance.” In a key passage from On the Road, excitement comes to life with characters who dance “down the street like dingledodies ... mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved...who never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.”

EVER THE TRANSIENT

In the key writing years from 1943 to 1955, when Kerouac was celebrating Manhattan with the passion of an insider, he made his home, such as it was for a self-described “lonesome traveler,” in Ozone Park and Richmond Hill, Jamaica. Whether living with his mother in Queens, or returning from his travels, he was always something of a transient in the city that was so central to his life and work. He hammered out the first teletype-scroll incarnation of On the Road between April 2 and 22, 1951 while staying in his second wife’s Chelsea flat, and when the New York Times told the world that On the Road in its published form was “an historic event” and Kerouac “the principal avatar” of the Beat Generation, he was temporarily based in a girlfriend’s apartment on the Upper West Side.

The fact is, The Town and the City and most of Visions of Cody (a prequel to On the Road), not to mention the long seminal letters to Neal Cassady, were written in the Kerouac family apartment above a drug store (since replaced by A Little Shoppe of Flowers) at 133-01 Cross Bay Boulevard (for more about Kerouac in Queens, see Patrick Fenton at insomniacathon.net). Meanwhile, The Subterraneans, Maggie Cassidy, and Book of Dreams were written at 94-21 134th Street, off Atlantic Avenue, a stone’s throw from the Van Wyck Expressway. It was there, in a frame house a long way from the urban architecture of Manhattan, that Kerouac gave Allen Ginsberg a lesson in writing “spontaneous prose.”

BONDING WITH THE CITY

Ginsberg and Kerouac’s paths first crossed on the Upper West Side, as you learn in Bill Morgan’s The Beat Generation in New York City: A Walking Tour of Jack Kerouac’s City (City Lights), which begins on the Columbia College campus, “where the Beat Generation first appeared like a wild seed in a city garden.”

Acccording to Kerouac’s autobiographical novel, Vanity of Duluoz (1968), however, it was during his prep school year (1939-1940) in the Bronx at Horace Mann School for Boys that he bonded with the city he traversed every morning on complicated two-hour subway rides from his step-grandmother’s house in Brooklyn. Besides enjoying the fullest measure of football glory he would ever know, he developed a taste for things that became features of Beat culture as he defined it. Introduced to jazz by a fellow student with whom he saw the big bands of Jimmy Lunceford and Count Basie at the Apollo in Harlem, he later interviewed Basie and Glenn Miller for the school paper. The Beat world of Times Square’s “junkies and criminals and whores” led him to skip school now and then to take in matinees at “huge carpeted movie film palaces” like the Paramount (“sitting right down in the tenth row front to watch the huge neat screen and the stage show that follows”), or watching French films starring Jean Gabin or Hollywood reruns with Errol Flynn at second-run movie houses on 42nd street.

When Kerouac introduces Times Square in The Town and the City, all sides of his vision of the city come into play along with fictional versions of himself (a seaman named Jack), Ginsberg (Leon Levinsky), Herbert Hunke (Junkey), Lucien Carr (Kenneth Wood) and William S. Burroughs (Will Dennison). It’s also at this point in the narrative that you begin to hear the familiar Kerouac music as he writes of Junkey resuming his “pale vigil” at the window of a 42nd Street cafeteria, “the same anxious vigil... from which the watchers of the Street could never turn their eyes without some piercing sense of loss, some rankling anguish that they had ‘missed out’ on something.” Even there, given the constraints imposed by editors and copyeditors at Harcourt, he’s still working with relatively “commonplace” terminology, especially compared to what happens in Visions of Cody when he opens his fiction to the hyped-up conversational cadenzas of Neal Cassady that will enliven and carry On the Road almost from the first written word.

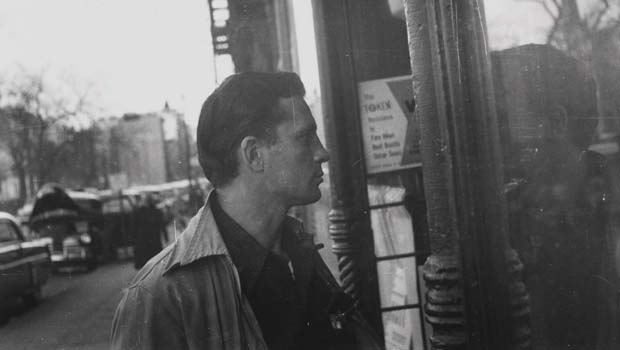

HANGING OUT ON CAMERA

Access “Beats in New York” on YouTube and you’ll see five minutes of Ginsberg and Kerouac hanging out on a summer’s day in 1959 in front of the Harmony Bar & Restaurant on the corner of Ninth Street and Third Avenue, a block up from St. Mark’s Place. Also shown are the family of the man presumably doing the filming, photographer Robert Frank, his wife Mary and their kids, along with Lucien Carr, who met Allen and Jack at Columbia, his wife Francesca and his kids (one of whom, Caleb, grew up to write The Alienest). First view of Jack, cigarette in hand, he’s pushing a doorbell and then gazing impatiently up, easily the most expressive, cinematic presence, the star of the scene, mugging, playing for the camera that the others, except the kids, are mostly ignoring. You see him again clowning inside the Harmony, making Ginsberg look studious by comparison. Kerouac provides a picture of the same street corner in Visions of Cody: “Building is ancient red—1880 redbrick—three stories— over its roof I can see cosmic Italian old-fashioned eighteen-story office block building with ornaments and blueprint lights inside that reminds me of eternity, the enormous house of dusk where everybody is putting on their coats—and going down black stairs like fire escapes to eat supper in the dungeon of Time.” The Harmony appears “in crimson neon upon the gray sidewalk” in the next paragraph.

ALL AROUND TOWN

Bill Morgan’s Beat Generation in New York remains the most enlightened and useful guide to Kerouac’s city. Here are some somewhat reconstituted highlights from a quick tour of the book; with few exceptions like Joyce Johnson’s description of Kerouac, most of the quotes are from the guide:

Dodge Hall/McMillin Theatre, where Gregory Corso, Peter Orlovsky and Ginsberg read from their work (Kerouac didn’t show up) on February 5, 1959, “the first acknowledgment of the Beats by Columbia.”

421 West 118th Street, a six-floor yellow brick apartment building where Kerouac lived with first wife, Edie Parker, and said “the happiest days of his life were spent.” Apartment 62, an unofficial hangout for the Beats, was where Lucien Carr brought William Burroughs up to meet Kerouac and where Kerouac and Ginsberg first met.

West End Bar, Broadway between 113th and 114th, which Ginsberg called “a replica of a Greenwich Village dive,” is where he first meets Neal Cassady, is rolled down the street in a barrel by Carr, and gets into a fight with two sailors defending Carr’s girlfriend.

New York Public Library main branch, Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, which houses “one of the best public collections in the world of books and manuscripts” by Kerouac, Ginsberg, Orlovsky, Burroughs, and Corso, who, as a boy, wrote his first poem there.

Bickford’s Cafeteria, 225 West 42nd, but long gone, was “the greatest single stage on Times Square” says Kerouac, who hung out there with Ginsberg, Burroughs, Carr and hustler poet Herbert Hunke, this being the nameless cafeteria mentioned in The Town and the City where Hunkey (Junkey) spent 18 hours a day sitting at the front window. It’s said that Hunke coined the term “Beat Generation.”

Hector’s Cafeteria, Times Square, also long gone, replaced by twin Cineplex movies, gave Neal Cassady his first glimpse of New York, with its “glittering counter,” and “decorative walls” and “noble old ceiling” of “ancient, almost Baroque (Louis XV?) plaster now browned a smoky rich tan color” (from Visions of Cody).

Rockefeller Center, where Allen Ginsberg worked as a copy boy for the Associated Press Radio News Service during the time he was having visions of William Blake in his apartment at 321 E. 123 Street in Harlem.

450 West 20th, Chelsea, where Kerouac lived with Joan Haverty and wrote the first draft of On the Road on teletype paper. Look down 20th east toward Seventh Avenue for a view of corner where Neal Cassady (Dean Moriarity) turns on his way to Penn Station when last seen by Kerouac (Sal Paradise) at the end of On the Road.

92 Grove Street, where Carr lived and Kerouac often stayed. Writing in Desolation Angels, Kerouac called it “the most beautiful apartment in Manhattan...with a small balcony overlooking all the neons and trees and traffi cs of Sheridan Square.”

White Horse Tavern, Hudson and 12th, though mostly associated with Dylan Thomas, was also a hang-out of Kerouac’s from which he was sometimes given the bum’s rush. It was also the site of a confrontation between two of his girlfriends, Helen Weaver and Joyce Glassman, who prevailed.

Marlton Hotel, 5 West 8th Street, where Kerouac typed up the fi nal manuscript of Tristessa, his short novel set in Mexico City.

Eighth Street Bookshop, 32 West 8th, corner of MacDougal, “Greenwich Village’s Famous Bookshop,” the East Coast equivalent of City Lights, and the publisher of the early poetry of Ginsberg, Corso, Kerouac, Gary Snyder, and Leroi Jones, as Amiri Baraka was then known.

Howard Johnson’s, Sixth Avenue near Greenwich and West 8th, where Ginsberg arranges for Joyce Glassman to meet and “rescue” Kerouac, who was down and out, this being January 1957. In her introduction to Desolation Angels, writing as Joyce Johnson, she describes her fi rst sight of him “at the counter.... in a red-and-black-checked lumberjack shirt. Though his eyes were a startling light blue, he too seemed all red and black, with his ruddy, sunburned complexion and his gleaming dark hair.”

Gas Light Café, MacDougal Street, the fi rst café with poetry readings. Poets included Ginsberg, Corso, Jones, Diane DiPrima, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Ray Bremser.

The San Remo, “a center of Kerouac’s N.Y. social life,” according to Ginsberg, who conversed with Dylan Thomas there. In The Subterreaneans, Kerouac placed the San Remo in San Francisco and changed the name to the Mask.

222 Bowery, where William Burroughs lived for six years in an windowless apartment he called the Bunker.

170 E. 2nd, 206 E, 2nd, 704 E. 5th, are among the East Village apartments Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky lived in between 1958 and 1965, in between long periods in India and Tangiers. It was at 704 E. 5th that Ginsberg took his last photographs of Kerouac.

Tompkins Square Park, between Avenues A and B, another real-life meeting place Kerouac moved to San Francisco in The Subterraneans.

408 E. 10th, Apt. 4C, where Ginsberg and Orlovsky lived from 1958 through 1965. Ginsberg wrote some of his bestknown poetry there while becoming politically involved and internationally famous.

404 E. 14th, above the McDonald’s, a building owned by painter-poet Larry Rivers. Ginsberg bought a loft here in the fall of 1996 with the money made from selling his archive to Stanford. In March 1997, at Beth

Israel Hospital on E. 16th, he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. He died at home, “surrounded by family, friends, and old lovers,” on April 5, 1997.

Inspired by Ginsberg’s breakthrough poem, the East Village’s HOWL! Festival was founded in 2003 “to honor, develop, create and produce” and to “preserve, and advance the art, history, culture, and counterculture unique to the East Village and Lower East Side.”

Jack Kerouac was born, March 22, 1922, and died October 21, 1969. His hometown, Lowell, Mass., planned a series of events to celebrate to what would have been his 93rd birthday.