Updating An Icon: Lincoln Center Has A New Leader And A New Look

By Anne Levin

There was a playground on the roof of the Manhattan elementary school Jed Bernstein attended in the early 1960s. From this vantage point during recess, he watched the first buildings of Lincoln Center rising on the site of a bulldozed Upper West Side neighborhood, just a few blocks away.

The little boy gazing down from the roof couldn’t have had an inkling that some five decades later, he would be at the helm of the prestigious performing arts complex that was taking shape before his eyes. Bernstein, now a well known Broadway producer and arts executive who was recently instrumental in bringing the Bucks County Playhouse back to life, begins his tenure as president of Lincoln Center this month.

By this past November, Bernstein was dividing his time between the Playhouse in New Hope, Pa. and his new office at Lincoln Center. “Having the chance to lead an iconic institution, and a unique institution, is very special,” he said during a recent interview in New Hope. “No other place in the world has Lincoln Center’s concentration of world-class performing arts.”

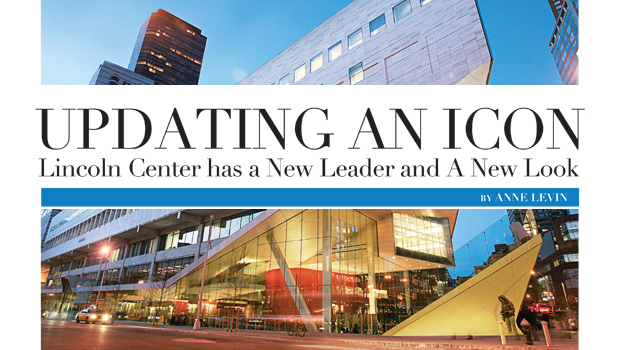

Bernstein’s appointment to succeed longtime Lincoln Center president Reynold Levy comes near the end of a $1.2 billion renovation of the 16.3-acre campus. Designed to make the world-class arts center—the largest and most comprehensive in the world—more open, accessible, user-friendly, and aesthetically pleasing, the project will be complete once Avery Fisher Hall, home to the New York Philharmonic, is renovated. Patrons and members of the public can now find places to hang out and relax as well as performances of opera, ballet, theater, film, jazz, chamber, and orchestral music to attend.

There is the David Rubenstein Atrium on Broadway, which has a central box office as well as a café with plenty of tables and free wifi. There is the Lincoln Ristorante, a pricey dining destination behind Avery Fisher Hall, with a tilting, grass-covered roof that invites lounging and sunbathing during warm months. The front of Alice Tully Hall, once boxy and forbidding, is now an airy, glass-walled gathering space, home to another popular café and seating area.

At the entrance to Lincoln Center’s main plaza, some of Columbus Avenue is now sunken to a drop-off lane below ground, with direct access to the basement concourse. The fountain that is the plaza’s focus has been redesigned with new technologies for special-effect water shows. Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the lead architects of the entire development project, have designed a sculpturally striking bridge that spans West 65th Street near Amsterdam Avenue. At the Juilliard School, a studio with large windows allows passersby to watch dance students in action.

Though much of the revamping of Lincoln Center has been completed, the urgency to raise money never goes away. “There is tremendous financial need on an annual basis, and there is always the challenge to identify new revenue streams,” said Bernstein who, as a theatrical producer and former head of the Broadway League trade association knows how to coax contributions out of investors.

Bernstein, 58, began his career in advertising, working for the firms Wells Rich Greene, Ogilvy & Mather, and Ally & Gargano. Switching his focus to theater was a natural progression for him. “I grew up on the Upper West Side in a family that valued art,” he said. “I was taken to ballet, opera, and classical music at an early age, often at Lincoln Center. We were not a family of significant means, and we could access the arts easily. If I can communicate to others and facilitate for others the joy and satisfaction of the arts that I grew up experiencing, that’s not a bad goal.”

When first approached about taking on the Lincoln Center presidency, Bernstein was surprised. But he came around quickly. “I was kind of baffled at first. I thought, why me? But the more time I spent with the head-hunter and the chair of Lincoln Center, the more I understood,” he said. “Sharing my love of the performing arts with people makes me the happiest. And one thing I’m good at is connecting with people and seeing ways to build relationships, being entrepreneurial about how to make opportunities happen.”

When it was conceived in the 1950s, Lincoln Center was the first arts complex of its kind. In his book The Lincoln Center Story, Alan Rich writes that one would have "to run the clock back to a Medici palace in Renaissance Florence" to find anything comparable in the world. A neighborhood of midtown Manhattan tenements known as Lincoln Square, which was the inspiration for the musical “West Side Story” and later served as a location for the film, was razed to make room for the complex.

The overall design was assigned to architect Wallace K. Harrison, who also designed the Metropolitan Opera House. Philharmonic Hall (now Avery Fisher Hall) is credited to Max Abramovitz; Philip Johnson did the New York State Theatre (now the Koch Theatre); Pietro Belluschi designed the building for the Juilliard School and the chamber music auditorium Alice Tully Hall; and Eero Saarinen designed the Vivian Beaumont Theater.

Philharmonic Hall was the first to open on September 23, 1962, with a gala concert of newly commissioned works by composers Aaron Copland, Paul Hindemith, and Samuel Barber, conducted by Leonard Bernstein. Other buildings and public spaces followed over the next seven years. There are 11 resident organizations: The New York Philharmonic, The New York City Ballet, The Metropolitan Opera, The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, The Film Society of Lincoln Center, The Juilliard School, The School of American Ballet, Jazz at Lincoln Center, the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Lincoln Center Theater, and Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts. Several popular annual events are produced by Lincoln Center, including the Mostly Mozart Festival, the annual Lincoln Center Festival, and Midsummer Night’s Swing, which brings hundreds of amateur swing dancers and live bands to the plaza each June. Outside companies such as American Ballet Theatre and the Paul Taylor Dance Company also perform at the complex.

As the new Lincoln Center president, Bernstein has his work cut out for him. There is Avery Fisher Hall to renovate, at a cost that has been estimated at more than $300 million. An original plan, now abandoned, tapped British “starchitect” Norman Foster for the job. But concerns about raising the necessary funding have sent it back to the drawing board, and a new architect has yet to be named. As always, there are donors to court and government support is always a challenge.

“I see the job of our organization, because I don’t think of it as just me, to try and provide the resources to allow not only ourselves, but all of our constituent partners to present great art,” he said. "But I'm so humbled to have the chance."

Bernstein is especially intent on arts education. “Education is absolutely critical,” he says. “Exposing kids to the arts—not because they’ll become professionals but because of the way it can help them in other parts of their lives—is something I’m very interested in. And we in the arts world have not made that argument enough.”

While not a practicing performing artist himself, Bernstein has a healthy respect for those so gifted. "Throughout my whole life, I've always had a crush on talent," he said. "You put me next to a baseball player, or the best coin collector in the world, and I'm interested. My role, when it comes to the arts, is to help provide the resources. That's what I was put here to try to do."

Settled into his new office at Lincoln Center's Rose Building, Bernstein is in charge of bringing the performing arts complex firmly into the 21st century. But unlike those childhood days of watching from his elementary school roof, he'll be looking out instead of looking in.